The 1960 Presidential election was the closest in our lifetime. Although John Kennedy was declared the winner of the November 8, 1960 contest, there were significant issues of actual fraud in the election.

Tom Wicker of the New York Times later wrote “Nobody knows to this day whom the American people really elected president in 1960. Under the prevailing system of John F. Kennedy was inaugurated, but it is not at all clear if this was really the will of the people, or, if so, by what means and margin that will was expressed.”

Nixon himself later revealed: “Of the five presidential campaigns in which I was a direct participant, none affected me more that the campaign of 1960. It was a campaign of unusual intensity. Jack Kennedy and I were both in the peak years of our political energy, and we were contesting great issues in a watershed period of American life and history.”

In mid-December 1960 Kennedy flew to Florida to meet with Nixon after the election, and Kennedy’s opening words in greeting Nixon were: “Well, it’s hard to tell who won the election at this point.”

Earl Mazo was a political reporter for the Herald Tribune. Forty years after the election, Mazo was still convinced that the Democrats had stolen the election, telling The Washington Post in 2000: “There’s no question in my mind that it was stolen. It was stolen like mad. It was stolen in Chicago and in Texas.”

Immediately after the election, Mazo conducted his own investigation, first going to Chicago, obtaining lists of voters in precincts that seemed suspicious and checking their addresses.

“There was a cemetery where the names on the tombstones were registered and voted. I remember a house. It was completely gutted. There was nobody there. But there were 56 votes for Kennedy in that house.”

Mazo then turned his attention to Texas, where he uncovered similar Democratic “electoral shenanigans.”

Mazo’s investigation revealed that in Texas, which Kennedy carried by 46,000 votes, a minimum of 100,000 votes officially tallied for the Kennedy-Johnson ticket were “nonexistent,” and in Chicago, “mountains of sworn affidavits by poll watchers and disgruntled voters” were testimony to the cheating. Kennedy had carried Illinois by only 8,858 votes out of 4,757,409.

Mazo began writing what he and his editors envisioned as a twelve part series on the election fraud in Chicago and Texas. Within a month, he had published the first four parts in the series. The articles were reprinted in papers across the country, including The Washington Post.

Mazo’s work caught the attention of Richard Nixon.

In the first week of December 1960, Nixon met with Earl Mazo. At their meeting, Nixon told Mazo: “Earl, those are interesting articles you are writing—but no one steals the Presidency of the United States.” Mazo described his reaction: “I thought he was kidding, but he was serious, I looked at him and thought, ‘He’s a goddamn fool.’”

But Mazo soon realized that never was a man more deadly serious. They spoke for over an hour about the campaign and the odd vote patterns in various places. Then, continent by continent, Nixon “enumerated potential international crises that could be dealt with only by the President of a united country, and not a nation torn by the kind of partisan bitterness and chaos that inevitably would result from an official challenge of the election result.” Yet Nixon could not convince Mazo to drop the story, so he called the reporter’s bosses at the Herald Tribune and implored them to stop running the series. Mazo’s editors pulled him off the story.

Of course, Nixon knew there were good legal grounds for a challenge. President Eisenhower was even willing to raise money from his friends to support a legal challenge. But while Nixon’s heart told him to do it, his head said no.

Through it all Nixon put decency before politics. He rejected a recount and did not challenge the outcome.

Nixon explained his two fundamental reasons:

“One, it would have meant the United States would be without a president for almost a year before the challenges in Illinois and Texas could be taken. I felt that the country couldn’t afford to have a vacuum in leadership “for that period. Two, even if we were to win in the end, the cost in world opinion and the effect on democracy in the broadest sense would be detrimental. In my travels abroad, I had been to countries in Latin America, Africa and the Far East that were just starting down the democratic path. To them, the United States was the example of the democratic system. So if in the United States an election was found to be fraudulent, it would mean that every pipsqueak in every one of those countries would be tempted, if he lost the election, to bring a fraud charge and have a coup.”

The election of 1960 was a great blow to Nixon’s mother Hannah. She was stoic, but she couldn’t fully hide her disappointment. Knowing her son would never stand for a recount, she simply stated: “It must be God’s will. We will have to accept it.” Nor did Hannah ever say anything derogatory about President Kennedy or any of his family. “It just wasn’t in her makeup to be that kind of person.”

Nixon had class. He was the sitting Vice President and he did not want to do anything seen as impeding on Kennedy’s limelight as Kennedy prepared to take office. At the same time, family friend Roger Johnson recognized that Richard and his family were “very, very disappointed.” But he also saw that Nixon “handled himself beautifully” during the transition period. Having just suffered his first political defeat in 14 years, and with everyone clamoring for Nixon to challenge the election results, instead Nixon hosted a huge Christmas party in his home on December 16, 1960 for hundreds of friends from the Eisenhower Administration, media, and presidential campaign.

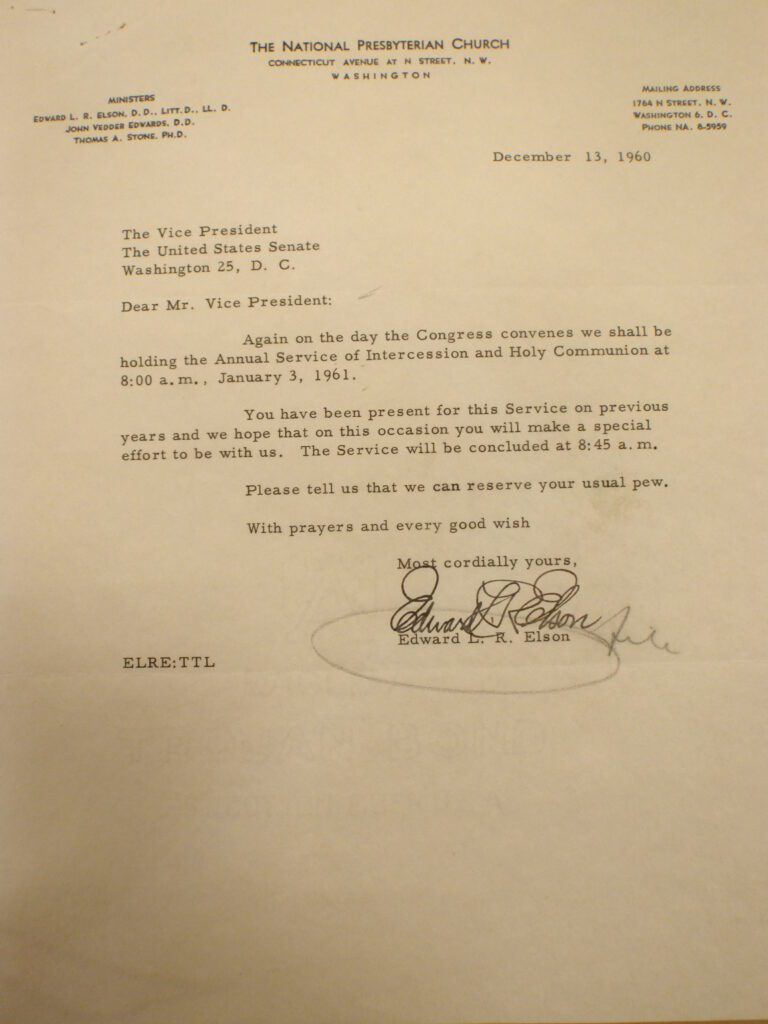

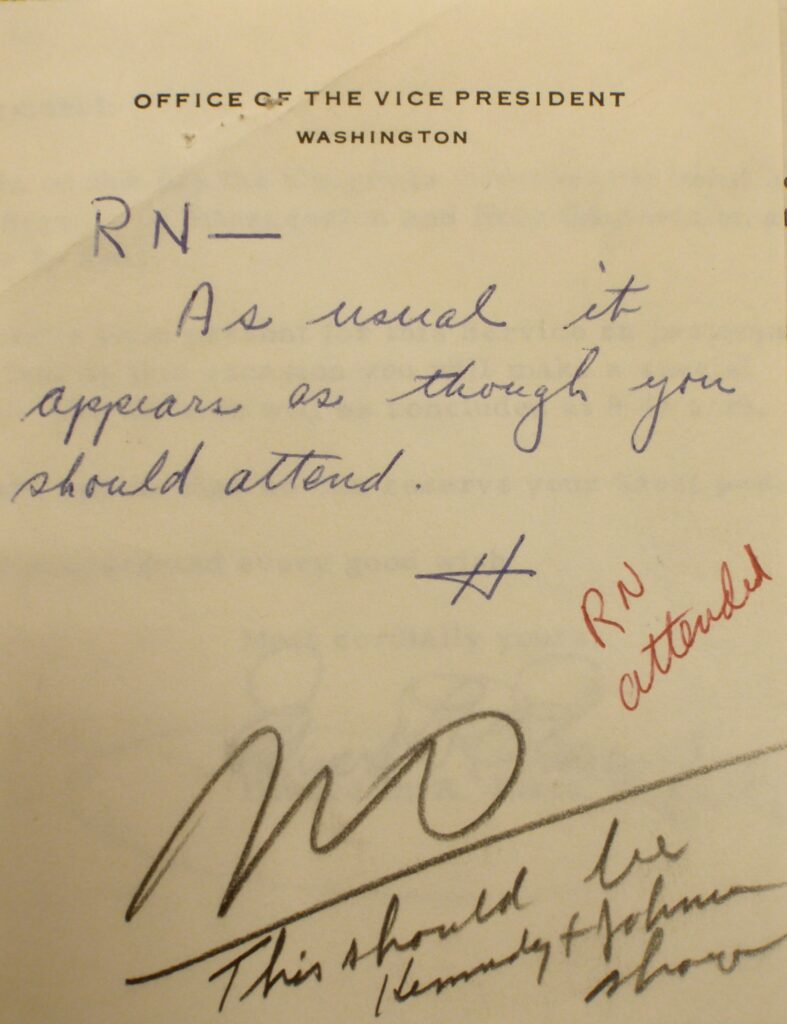

Nixon was invited to the Annual Service of Intercession and Holy Communion on January 3, 1961, at the National Presbyterian Church. Minister Edward Elson offered to reserve Nixon’s “usual pew.” Nixon initially responded “No, This should be Kennedy and Johnson’s show,” although ultimately, he relented and attended.

On January 6, 1961, Nixon addressed a Joint Session of Congress as Vice President. He had the nearly unprecedented duty where, for the first time in a hundred years, a candidate for the Presidency announced the result of an election in which he was defeated and announced the victory of his opponent.

Nixon told the Congress: “I do not think we could have a more striking and eloquent example of the stability of our Constitutional system and of the proud tradition of the American people of developing, respecting and honoring institutions of self-government. In our campaigns, no matter how hard-fought they may be, no matter how close the election may turn out to be, those who lose accept the verdict, and support those who win.”

Nixon then stated that, having served in government fourteen years, a period which began in the House, continued in the Senate and then as Vice President, “it is indeed a very great honor for me to extend to my colleagues in the House and Senate on both sides of the aisle who have been elected, to extend to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, who have been elected President and Vice President of the United States, my heartfelt best wishes, and to extend to you those best wishes as all of you work in a cause that is bigger than any man’s ambition, greater than any Party. It is the cause of freedom, of justice, and peace for all mankind.”

Quite a lesson for us all, indeed!